The concept of organoids was born in 2008, following the publication by Eiraku et al. of cortical neuroepithelia generated from self-organizing cultures of embryonic stem cells. A year later, in 2009, Sato et al. cultivated tissue-derived adult stem cells into complex 3D intestinal ‘organ-like’ structures in one of the most famous publications in the field. Two years later, Spence et al. showed that intestinal organoids can also be derived from human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells.

Almost 20 years later, here we are. Organoids are a reality in biomedical research, but are still waiting to leap as a routine model in preclinical phases. What’s holding them back?

The answer lies in the details of how organoids are grown, maintained, and standardized. Understanding these protocols and how automation can improve them is key to moving from promise to practice.

Organoid Culture: Definition, Applications, and Research Potential

Organoids are three-dimensional (3D), self-organizing cellular systems derived from pluripotent or adult stem cells that reproduce key features of their tissue of origin. Stem cells aggregate, self-organize, and differentiate within a 3D extracellular matrix (ECM), giving rise to mini-organs that reproduce tissue-specific architecture, contain various cell types, and perform similar functions to their in vivo counterparts.

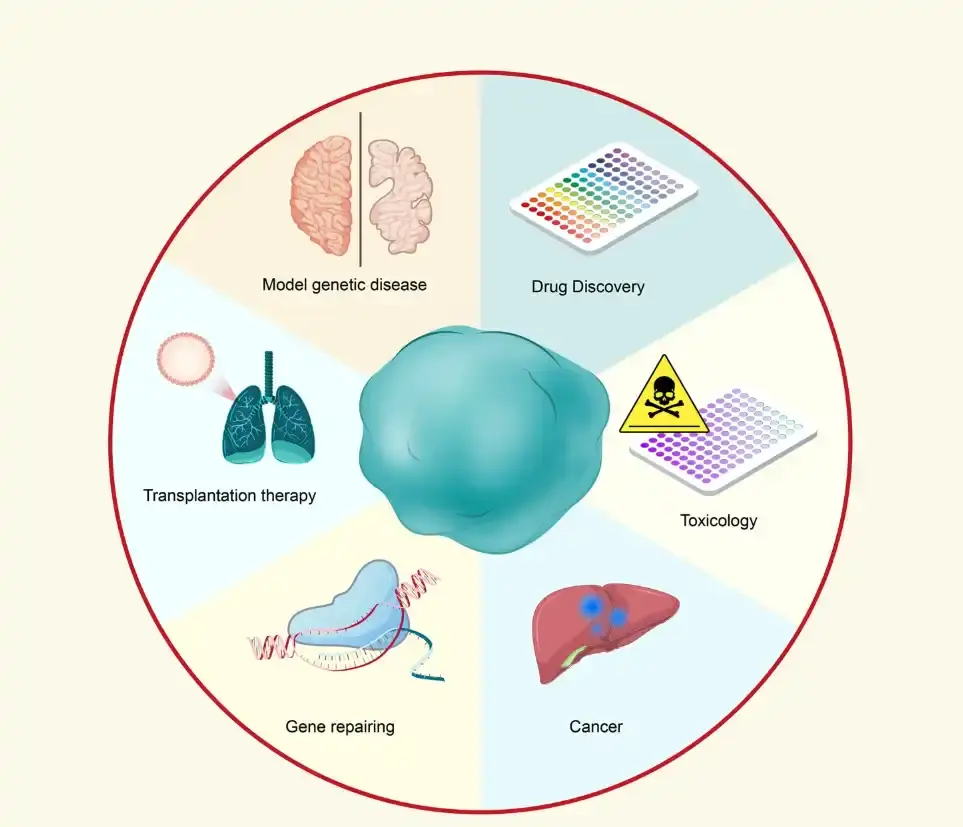

Recent advances have positioned organoid 3D culture at the intersection of developmental biology, precision medicine, and regenerative therapies. Human organoid applications include preclinical drug testing, toxicology, and even early-phase clinical trials. They offer patient-specific insights that reduce reliance on animal testing and improve predictive accuracy in pharmacological research. Organoids derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) can replicate multiple cell types within a given organ, enabling high-fidelity disease modeling for tissues such as the brain, liver, intestine, and kidney.

Figure 1. Applications of organoid technology. Source: Tang XY, Wu S, Wang D, Chu C, Hong Y, Tao M, Hu H, Xu M, Guo X, Liu Y. Human organoids in basic research and clinical applications. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022 May 24;7(1):168.

One of the most transformative applications of organoids lies in drug discovery and development.

90% of drugs fail in clinical trials after succeeding in preclinical phases. This failure is attributed to a lack of clinical efficacy and unmanageable toxicity in 70-80% of the cases, which reflects a long-standing gap between preclinical testing and clinical reality. Organoids can fill this need.

Patient-derived organoids can replicate genetic mutations, signaling pathways, and tissue-specific responses, allowing for testing compounds directly on models that reflect individual patient biology. This approach enhances both safety and efficacy assessments before clinical trials begin and reduces the reliance on animal models, ameliorating the ethical burden and the resources needed for drug development.

Organoid Culture Protocol: Step-by-Step Guide to 3D Growth

The foundation of successful organoid culture lies in three interdependent elements: cell source, extracellular environment, and nutrient composition. Depending on the goal, organoids can be established from pluripotent stem cells (embryonic or induced) or adult stem cells isolated from tissue biopsies. Each cell type requires specific cues to initiate differentiation and spatial organization. Pluripotent stem cell-derived organoids, for example, undergo germ-layer induction followed by exposure to signaling factors that guide tissue-specific development. Adult stem cell-derived organoids typically form more rapidly and exhibit adult-like phenotypes.

Although protocols vary depending on the organoid type, basic organoid culture protocols include the following steps:

- Cell source preparation: After selecting the stem cell source, verify pluripotency or lineage identity using immunostaining or flow cytometry before initiating 3D culture. Dissociate cells gently into single-cell suspensions or small aggregates to preserve viability.

- Matrix embedding: Mix the prepared cells with an ECM such as Matrigel, and pipette small domes (20-40 µL) onto pre-warmed culture plates. Allow the matrix to solidify at 37°C before adding the culture medium.

- Medium composition and supplementation: Once the matrix is solidified, add the medium. Use a basal medium such as advanced DMEM/F12 supplemented with B27, N2, GlutaMAX, and antibiotics, and add key growth factors depending on the organoid type.

- Culture incubation and monitoring: Maintain at 37°C with 5% CO₂ and appropriate humidity.

Observe daily under an inverted microscope to assess morphology, spheroid integrity, and contamination. Organoid formation timing depends on the cell source and differentiation stage.

→ Each organoid type requires its own approach. For specialized organoid culture protocols for brain, intestinal, liver, and other organs, we recommend exploring the Organoid Protocol Collection by Nature Protocols.

Quality control is critical at each step. Morphological monitoring ensures that organoids maintain shape and size uniformity, while organoid viability assays, such as ATP quantification and immunostaining, confirm cell viability and lineage fidelity.

Variations in manual pipetting, media preparation, or incubation conditions can introduce batch effects. Integrating automated liquid handling and quantitative imaging not only reduces human error but also expands the number of samples and conditions that can be tested simultaneously, turning what was once a manual, limited process into a scalable workflow for true protocol optimization and standardization.

Optimizing Organoid Growth, Viability, and Automation for Reliable Results

Automation is a key asset for optimizing organoid growth, viability, and especially reproducibility. Manual workload limits iterative optimization, while automation allows designing and running multiple experiments to test different culture conditions. Introducing variations in media composition or growth factor concentrations helps identify the parameters that yield the most consistent and biologically relevant organoids, accelerating discovery and standardization.

The reproducibility is not only a technical improvement but a scientific necessity. By ensuring stable growth conditions and minimizing batch-to-batch variability, automated workflows enable high-throughput screening and long-term culture experiments with statistically reliable data. In the context of regulatory-grade research, such as toxicology studies aligned with the FDA’s roadmap to reduce animal testing, automation supports traceability and data integrity across the experimental pipeline.

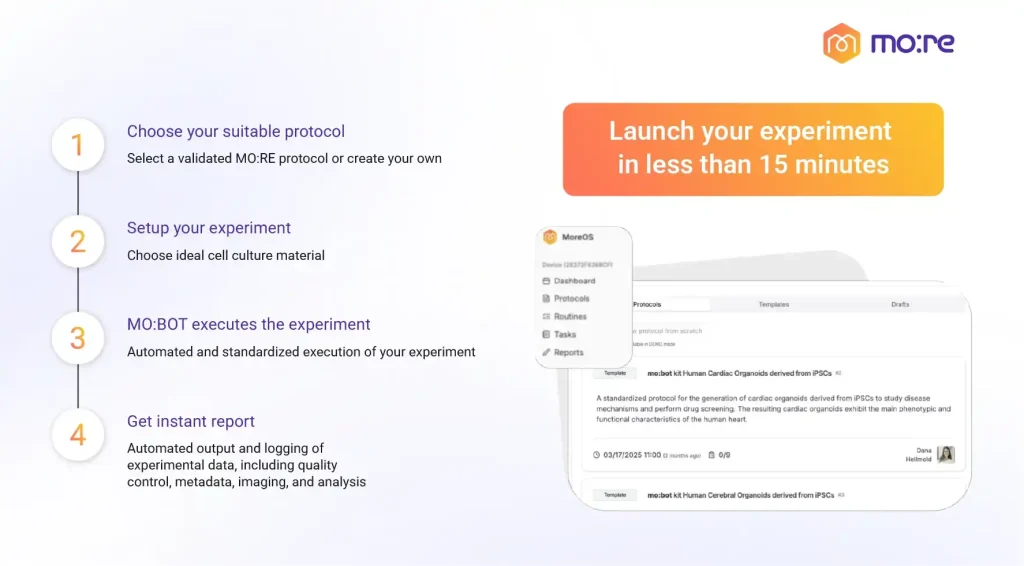

MO:BOT exemplifies this transformation by merging robotics, software, and biological expertise into an integrated workflow designed for reproducibility and scalability. Our platform automates critical steps such as cell seeding, medium exchange, imaging, and data collection, reducing human error while preserving organoid integrity.

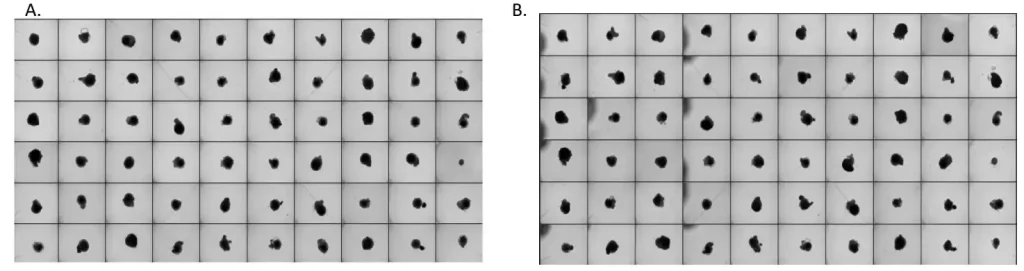

In a recent application note, we have demonstrated the automated maintenance of cortical organoids derived from human iPSCs in 96-well plates. Over several days of automated medium changes, the morphology and viability of organoids remained consistent (Figure 2). Bright-field imaging confirmed that the 3D architecture was maintained without aspiration or structural damage, and ATP assays indicated high cell viability across all wells. There were no differences in organoid area and roundness between automated and manual conditions, validating the precision of the platform’s pipetting system.

Figure 2. Bright field image overview of 96-well plates with 60 cerebral organoids from one batch before (A) and after 4 automated medium changes (B).

A distinct strength of our platform lies in its optimization capabilities. You can easily design and run parallel experiments to test different culture conditions and optimize your organoid culture. We have also pre-verified biological protocols for 9 different organoids and integrated them within our platform, so there is no need to optimize them if you are not an expert. You can access ready-to-use organoid differentiation methods directly on the system, accelerating experimental setup and standardizing outcomes across laboratories.

As protocols evolve and automation becomes standard, the field is moving toward a new level of reliability and scalability. We aim to make organoid research more consistent, efficient, and regulatory aligned. The future of organoid culture will depend on the balance between scientific rigor and automation.

Sources

Clinton J, McWilliams-Koeppen P. Initiation, Expansion, and Cryopreservation of Human Primary Tissue-Derived Normal and Diseased Organoids in Embedded Three-Dimensional Culture. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2019 Mar;82(1):e66. doi: 10.1002/cpcb.66.

Eiraku M, Watanabe K, Matsuo-Takasaki M, Kawada M, Yonemura S, Matsumura M, Wataya T, Nishiyama A, Muguruma K, Sasai Y. Self-organized formation of polarized cortical tissues from ESCs and its active manipulation by extrinsic signals. Cell Stem Cell. 2008 Nov 6;3(5):519-32. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.09.002.

Sato T, Vries RG, Snippert HJ, van de Wetering M, Barker N, Stange DE, van Es JH, Abo A, Kujala P, Peters PJ, Clevers H. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009 May 14;459(7244):262-5. doi: 10.1038/nature07935.

Spence JR, Mayhew CN, Rankin SA, Kuhar MF, Vallance JE, Tolle K, Hoskins EE, Kalinichenko VV, Wells SI, Zorn AM, Shroyer NF, Wells JM. Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into intestinal tissue in vitro. Nature. 2011 Feb 3;470(7332):105-9. doi: 10.1038/nature09691.

Sun D, Gao W, Hu H, Zhou S. Why 90% of clinical drug development fails and how to improve it? Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022 Jul;12(7):3049-3062. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2022.02.002.

Tang XY, Wu S, Wang D, Chu C, Hong Y, Tao M, Hu H, Xu M, Guo X, Liu Y. Human organoids in basic research and clinical applications. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022 May 24;7(1):168. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01024-9.

Verstegen MMA, Coppes RP, Beghin A, De Coppi P, Gerli MFM, de Graeff N, Pan Q, Saito Y, Shi S, Zadpoor AA, van der Laan LJW. Clinical applications of human organoids. Nat Med. 2025 Feb;31(2):409-421. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-03489-3.

Yang S, Hu H, Kung H, Zou R, Dai Y, Hu Y, Wang T, Lv T, Yu J, Li F. Organoids: The current status and biomedical applications. MedComm (2020). 2023 May 17;4(3):e274. doi: 10.1002/mco2.274.